This article is the third in a series to highlight the five 2016 Digital Humanities Summer Faculty Workshop Projects sponsored by the Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities (AKIH), and co-organized by Northwestern University Libraries (NUL) and the Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences’ Multimedia Learning Center (MMLC). Each summer five faculty projects are chosen for their role in developing digital humanities pedagogical and research projects with meaningful roles for students.

Next up is Dr. Rebecca Zorach and her project on the “Chicago Mural Movement.” Her project used student assistance to catalog public art, specifically murals from the Black Arts Movement of the 60s and 70s, around the city of Chicago to create an interactive map that can be used for not only viewing mural images but also as a way to connect with other existing data sets like the CTA route map or census data to ask interesting questions about race, class, gentrification, and more.

Opening April 21 and running through June 18, 2017, The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern will be displaying work from the project as part of the “We Are Revolutionaries: The Wall of Respect and Chicago's Mural Movement” exhibit in the Katz Gallery.

I recently caught up with Dr. Zorach to see how her project and the exhibition are shaping up…

Q: How’s the project coming along?

RZ: At this point, the students and I have really been focused on putting the upcoming Block exhibition together—making choices about which images to include, doing research on those images, thinking about exhibition design and about what goes where so we can encourage some kind of audience interaction with the exhibition.

Can you tell us a little bit about the upcoming exhibit at Block based on your project and the idea behind doing it?

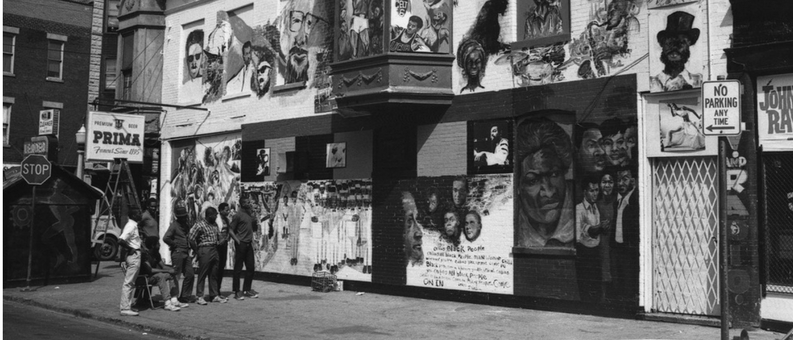

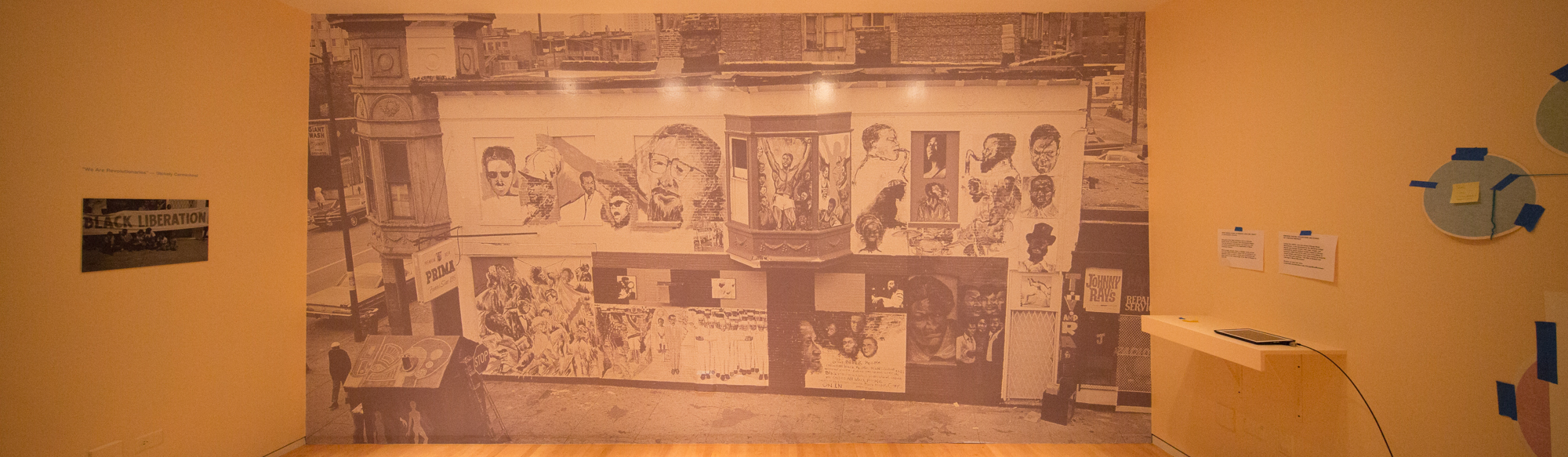

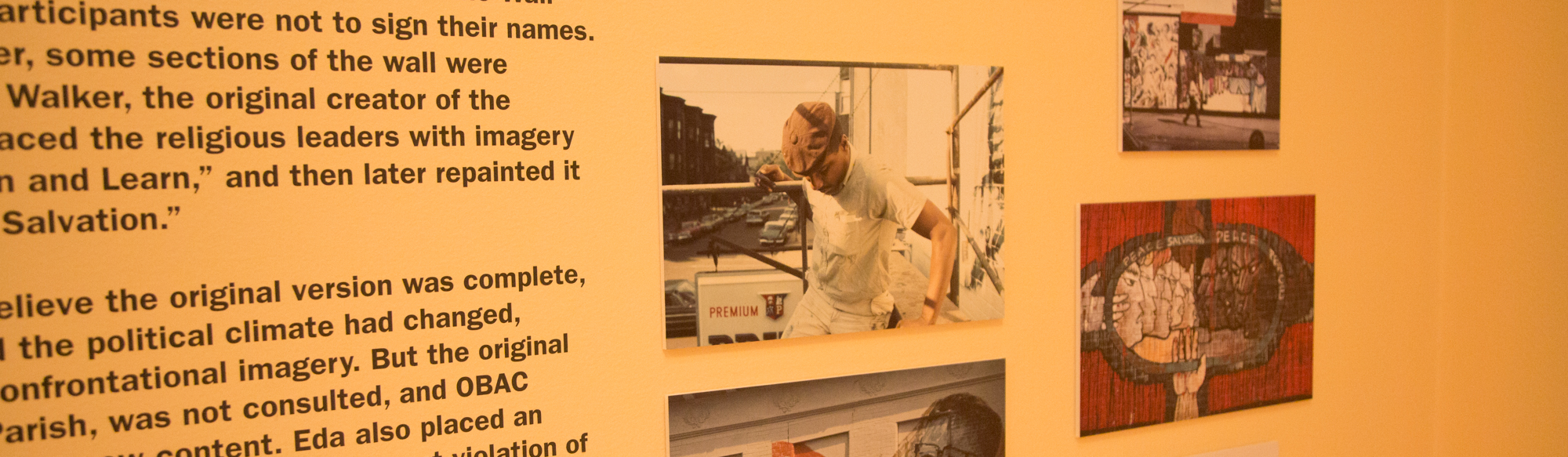

The idea for the exhibition arose out of work with other organizations planning events to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Wall of Respect. This was the 1967 mural painted on the South Side by the Organization for Black American Culture that set off the community mural movement in Chicago and around the country. The Block gave me the opportunity to do the exhibition with a class—a first-year undergraduate seminar. The students were new to college and didn’t necessarily know anything about art history when they began, but they researched the murals and chose images and themes and did a fantastic job. They studied exhibition design and gleaned some ideas from other exhibitions. That process inspired an interactive component (the large mural wall that visitors can post ideas on about what a contemporary Wall of Respect would look like) as well as a creative way of displaying the themes they identified in the murals.

Image: Robert Abbott "Bobby" Sengstacke, Untitled, Chicago, Wall of Respect, 43rd and Langley, [detail] (c.1970), Courtesy of The Sengstacke Archive and Getty Images, University of Chicago

How were digital tools used in the course, and how are you using them as you prepare the exhibition?

We used digital tools in the course as a way of introducing how to think about the presentation of visual art. For example, we’d talk about how a caption can make a difference in the interpretation of an image. That’s so much easier to do now with something like PowerPoint than what we did 20 years ago in art history. Students in the class would come up with their own comparisons of captions with an image to ask how the caption changes the viewing of an image, and what does this other caption with the same image tell us.

The final project was to individually create a StoryMap around a topic of their choice that traces a story through a series of images to be included as a digital component of the exhibition.

Can you describe what visitors will experience when visiting the exhibit?

We have a series of images of the Wall of Respect that are arranged in a way that the students have come up with that really focuses on the community involvement in its creation and events around the mural after it was made. That’s one long wall of the exhibition. Opposite will be another long wall that will have images of 18 other murals that came out of the movement which started with the Wall of Respect and are keyed to a map of Chicago. This wall also gives a sense of the mapping work that was done as part of the class.

Earlier you mentioned audience interaction – how will that work?

In the back right corner of the gallery, there’s a little shelf that has an iPad preloaded with the StoryMap website the students created with Weinberg’s Media and Design Studio. Guests can interact with a map of Chicago, clicking on specific mural images to learn more about their story.

Another interactive component utilizes the wall-sized print of the Wall of Respect. On that same back shelf, there will be a stack of sticky notes and a pen. Once visitors have an idea of the story – what went into the Wall and what it represented – they are encouraged to write down what would be their own contribution if the Wall of Respect were being created today. Our hope is that by the time the exhibit closes, the back wall will be filled with their contributions.

What do you hope people walk away with after attending the Block exhibit?

I hope they walk away with a better historical understanding of the Wall of Respect – that a group of black artists in the late 1960s got together and made this visual intervention into a distressed neighborhood that was about a wall of black heroes and heroines. And then how that experience sparked a movement all around the city where artists were working with neighborhoods and communities to make these murals with the goal of somehow representing something about that community because many of the issues that the artists were grappling with still continue today and need attention today.

When you think about your work on this project in relation to humanities instruction, what do you see as the benefit of moving into a more digital realm?

It makes some things easier and faster when making different kinds of connections but in a in a fairly traditional humanities vein. When I wrote my dissertation, the Perseus Project [ed. a digital Classics library] was newly available and it allowed me to search Classical texts without needing to be a Classics expert. I was studying Renaissance Art and just being able to do a keyword search for words in Latin texts where you know there are a lot of references that might be relevant but wouldn’t jump out to anyone without an encyclopedic knowledge of Classical texts opened up possibilities previous generations couldn't access. It made something possible that only a very small number of art historians had been able to do before.

Even on that basic level of what's available to us now, I think if we use new technologies with both imagination and a critical sensibility, there are all kinds of things that we can do with actual human ideas that we couldn't do before. The really new possibility would be to do things in entirely different ways. I think it's exciting to imagine what the capacity for new technologies might be without losing what's important and valuable about the humanities — how we might be able to explore questions that were previously impossible to ask.

The “We Are Revolutionaries: The Wall of Respect and Chicago's Mural Movement” exhibit displaying Dr. Zorach’s work with her students is available to visit April 21 to June 18, 2017, in the Block Museum’s Katz Gallery during normal gallery hours. Plan your visit today!